Home Page

CHAPTER 1

1346; a Sutton Villager - The early chapel of Sutton

Settlement of Wawne to 1346

Sudtone of Domesday Book 1086 - 1150

The founding of Meaux Abbey

A Visit to the Abbey in 1346 - William le Gros

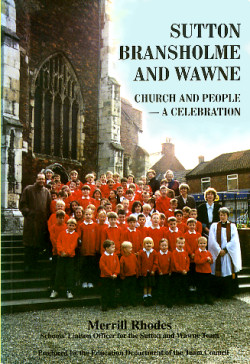

As we look forward to the next Millennium in this fast-moving age, it is

also fascinating to look back from time to time and imagine ourselves

in a familiar place, but in a long-forgotten era.

Sutton Church celebrates the 650th anniversary of its foundation

on 12 September 1999. As we gaze at the ancient edifice on a slight eminence

in the midst of a bustling and noisy village, we wonder what is was like to live

here in the mid-1340s just before this place of worship was built, when

a humble chapel stood on the site. Let us journey back to 1346 . . .

Who are our neighbours? What are our houses made of? What do we eat?

What kind of life do those 'White Monks'1

lead who keep that grange near the chapel, and till their land so

assiduously, and tend their sheep? What impact will the

granting of the Charter by Edward I to Kingstown upon Hull nearly 50

years ago have on the future of Sutton? How is our own Sir John,

Lord of the Manor, faring at Crécy in the wearisome war against France?

Will the king ever repay Sir William (de la Pole) for all the money he's

loaned him for the campaigns? And (most frightening of all) will

the 'Black Death', now widespread in Europe, invade our vulnerable shores?

Perhaps we should enter our little chapel and ask for the mercy and

deliverance of almighty God. This building, perhaps nearly two hundred

years old now, is certainly run down. John de Sutton is right to be wishing to re-build it.2 His wife, Alice, says that she can see from the window of the Manor how the roof is in danger of collapse.

The sturdy font, though, standing on the floor just inside the door, looks

good for another few hundred years yet. Built of stone around 1200, it bears

nail-head patterning around the rim, and its flat lid is securely locked to keep

the witches from taking the water.

Font of Early English Period

3

modern pic shows font in present position

There aren't any seats; we just kneel or stand on the rush-strewn

floor. Some of the older ones sit on the stone seats running round the walls.

Through the screen dividing the nave from the chancel we can

just see the priest standing at the heavy stone altar, and hear him intoning the

Paternoster4

- in Latin of course.

This first chapel at Sutton was built in the time of Sayer de Sutton. Before this, the few villagers

(18 at the time of Domesday Book) used to walk to the Mother Church at Waghen (Wagene/Wawne)

where the vicar lived. Waghen was bigger than Sutton then. Even after we had this chapel,

for years the villagers had to travel to Waghen for the major festivals, and all the burials had to be held there.

Our ancestors resented paying the rights and fees of baptism, marriage and burial to Waghen, when they had their own

chapel to maintain as well. It wasn't until about 50 years ago, in 1291, that the rector of Sutton

church at last received proper financial dues from his parishioners, but we still have to traipse

all the way to Waghen to bury our Sutton folk - and it's hard when the weather is bad.

There have been settlements at Waghen for hundreds of years. An axe-head dating from the

Stone-Age was found there. The Romans established a camp to the north of the village. Then

when the Angles and Saxons invaded, they called the land Waywyn, and built their homes of thatch and wattle.

They farmed the land on the high ridge that ran from the village all along the highway to Sutton.

At the time of Domesday Book in 1086, the ridge was surrounded by waters and marshland,

and at high tide Waghen became entirely separated from Sudtone, as it was called then.

Some of the little holms like Bransholme and Seffholm stood out of the water and people have lived there, I believe.

Map of Domesday 1086 (after Blashill)

The Lords of the Manor and the monks set about draining the land by

digging ditches and dikes. In fact the monks changed our landscape for

ever . . .

It was two hundred years ago (just before our little chapel of Sutton

was built) that remarkably, out of all the dreadful havoc that King

Stephen was wreaking on the country, plundering and burning indiscriminately, and

massacring whole village communities, that small religious groups began

what can only be called a monastic revival.5

St Bernard of Clairvaux had established the first Cistercian House in

1098, and the Movement flourished, slowly here in Yorkshire, but the

magnificent abbeys of Fountains, Jervaulx, Rievaulx and Byland bear

witness to the remarkable energy, organisation and commitment of the Order. Finest

of all in our eyes is the spectacular abbey of Meaux. Occasionally, when the land is not under water -

which it often is, despite the efforts of the monks and Lords of the Manor to dig ditches

and drains - we walk the five miles along the byway to the abbey.

Fortunately, we are on slightly raised ground here, but elsewhere the monks' properties have suffered terrible losses through persistent flooding, especially at Ravenserodd.7

Waghen had become a busy place by 1160 when the monks employed nearly

200 tenants there, all paying rent, and providing the abbey with corn

and hay, bread and beer, geese and hens. Soon afterwards, a grange or farm with

buildings was established in the village. These were followed by the wool manufactory and mills,

a further source of income. Smiths and skin workers are all employed in Waghen.

The estates produce grain, cereals and poultry. The monks have water mills and fisheries by the river bank.

All along the footway between Sutton and Meaux we pass flocks of sheep belonging to the abbey.

Oats and wheat, barley and beans, and fields of corn ripen in due season. When at last we reach Meaux, we always stand and stare at the splendid abbey church.

Despite the abbey's grandeur, though, the monks are always in debt. Hugh of Leven is the abbot there now, and not long ago he

thought up a new scheme to pull in some revenue.

He employed a sculptor to fashion a new crucifix for the choir of the

converts.8 The sculptor gave due reverence to his contract, and worked

on the finer parts of the image on Fridays only, living simply on bread and water.

To enable him to beautify the figure, he used a naked model.

Sure enough, when the crucifix was completed, it was found to

have miraculous powers. Men came from far and near to worship before it

with excellent results - their piety increased, and inspired them to offer

alms to the monks, which increased their piety still further. Many of our

husbands went, but we women were debarred, because of the rules of the

Cistercians. Abbot Hugh then obtained special permission for women

'of good character' to enter the monastery church. Naturally enough,

we couldn't go into the cloister or dormitory, but we were allowed to

look at the magnificent church and some of the other buildings.

The colours are amazing - wonderful tiles all made by the monks and brethren.

The Monks' Choir is dazzling.9 We could

not believe it! We kept going from room to room gazing and exclaiming!

The crucifix is a real work of art.

Two monks working in the library showed us some of their

books, all beautifully written on vellum. One of them is writing a Vita Edvardi Rex10, about

when the monks allowed the King the town of Wyke for only £47 in 1293. Of course

it's been known as Kingstown since then, but the monks made sure they kept

control of the market - very important financially with the stallholders' rents

coming their way, and supplying a ready outlet for the abbey livestock, wool,

cloth and corn. In his time, Edward I granted the abbey free warren11 in all their lands

outside the royal forests. The monks produce leather from the deer

hide, and furs from foxes and rabbits.

The monks gave us a lovely meal of fish and wine before

we left, and we bought a piece of their delicious cheese.12 After that, we had no

money for the collection plate - and soon afterwards Abbot Hugh stopped us going. But we'll never forget that visit to the monastery as long as we live.

On a quiet day in Sutton we can hear the great bell called Benedict, tolling

from the belfry of the abbey church, and it always reminds me of that

exciting day.

Part of Mosaic Pavement found 1760

Occasionally we walk past the abbey church and watch the

lay brothers at work at North Grange. The tile kilns are still there,

though most of the mosaic floor tiles were fired last century.13

When I was young, I remember them making the tiles for the roof of the abbot's new house.

It's amazing to think that all that land would probably

still be a hunting park if William the Fat had had his way. He

was Earl of Albemarle and Lord of Holderness. He owned several estates,

including one near the hamlet of Melsa, now Meaux. When he

was getting on in years, in anticipation of future hunting delights,

thought he would like to create a deer park, and started to have the area

enclosed with a raised bank and broad ditch. We still call the land Park Dyke.

There was only one thing troubling William. He well remembered that as

a young man he had made a vow to go on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem,

but now he was too old and too fat - he couldn't even sit on a horse, he admitted.

To salve his conscience, he had given up some of his estates for the

founding of religious houses. But he felt this wasn't enough. On a visit to Fountains,

he confided his anxieties to a monk named Adam, an expert in monastic architecture.

The latter was quick to point out that the Earl could be excused from his vow if he

founded yet another monastic house on land chosen by himself in Holderness,

then quite devoid of monks. The earl agreed, and was duly granted dispensation from his vow.

However, he was horrified when the place Adam chose was his own hunting park at Meaux,

only recently acquired from John de Melsa. He demurred at length, but to no avail, for Adam was insistent.

We do not know whether Adam had second thoughts on that New Year's Day of 1151

when he as first abbot, and twelve followers, surveyed that

remote spot amid the barren wastes of Holderness, and realised that this simple,

mud-built dwelling must be their new home. The life was bleak and cold, their

diet was mean, and they nearly starved that first winter. But they were

encouraged by the local peasants, who must have been astonished at these men

of God at one moment chanting their offices, and the next tilling the soil with spade and pickaxe.14

Adam was no businessman, however. There was not enough money to support the novices and converts, and poor Adam was left with only his cowl to wear, having given away all his other clothing. The monks had to disperse for a while until they were given gifts of land from sundry benefactors.

Looking now at the splendid buildings, it is hard to visualise that mud-built house

of 1150, and close by, the two-storeyed wooden chapel. For decades the peace

and tranquillity for which the first Cistercians strove, was shattered

by the continuous building schemes.

"Everywhere peace, everywhere serenity, and a marvellous freedom

from the tumult of the world."15, wrote Aelred, abbot of

Rievaulx from 1147. How ironic! Now from March to October the mason and his

team would be busy at Meaux from 5am to 7pm, building refectory and

kitchen, lavatory and library, infirmary and offices, tannery and smithy. Only

when October was out was the unfinished work all covered with straw and

bracken to protect from frost, and left until the Spring.16

In those early years, much land was freely granted to the abbey by local

lords and peasants for the support of the community, on condition that

the monks should pray for the benefactor and his family.

Sometimes novices came to the abbey, having no intention of

being trained for the high monastic life, but, perhaps being old or frail,

wishing merely to spend their last years in peace in the convent.

These were usually men of important standing, thus bringing with them material gifts, often of land.

The monks were given quarries and farms; they were granted the ferry at Waghen for the transport of wool and produce.

Other land was granted by those setting out on crusade.

The monks would usually agree to return the land if the crusader came back - but he rarely did.

The monks are very astute at exchanging land of little use for

profitable acreage, and so increase their yield. They were very quick

to gain land here in Sutton in this way. The monks also buy land or

hold it on lease from farmers who have run into debt through bad management,

say, or high living. They hold property on some odd conditions, too;

they had a very nice house in Hedon in return for allowing the

counts of Albemarle to use their ferry across the Humber.

Now, the monks dominate all this area, and far afield as well.

Their trade in wool here and in Europe is renowned.

The Cistercian influence on our lives in this place

cannot be over-stated. Their love of God and

devotion to prayer is clear to us all.

The abbey is a true centre of worship, where praise, intercessions and

thanksgivings are offered constantly. Despite their constant craving

for yet more land, it would be unfair to diminish their religious

sincerity. The monks genuinely care for the sick and needy.17

Some poor souls go every day to the abbey gates for their food.

Tramps are given relief and shelter.The monks look after those who are ill in

their hospitals, and tend the victims of accidents and violence.

The abbey is acclaimed for its hospitality to merchants,

to travellers and pilgrims, all of whom have to traverse that difficult and sometimes dangerous byway, located as it is a good two miles from the highway to Beverley.

Neither can the skill, culture and expertise of the monks

be ignored. Apart from the incredible number of beautiful tiles in the Abbey, the monks wear gorgeous vestments, and fashion costly chalices and pattens. They have written wonderfully illuminated service books, as well as their splendid collection of classical, theology, music and history books in the library.

Some of the men are gifted musicians and architects.

These Cistercians introduced a new class of monks, known

as lay brothers. They are usually illiterate men who do much of the manual work of

the abbey. They assist in the building programmes and in the management

of the granges or farms, sometimes at some distance from Meaux itself.

They come back here on Sundays and feast days, when the abbey is very busy and lively.

Although generally from poor backgrounds, some of the brothers

are quite gifted. Apparently one of them, called John, is very artistic and some

of his paintings are displayed on the abbey walls.

Then there are the servants; I think the cellarer alone

has a staff of a dozen or so. As early as 1197 it appears that women

were already being employed on neighbouring estates,

for a house in Knottingley was given 'on condition that no women dwell

there', implying that women were usually employed.18

Women still work as servants in the granges and in the outer

court of the abbey. I'm told that women are sometimes paid to care for and teach

young orphans.

However, Meaux has become embroiled in interminable

disputes and litigations, and consequently the monks are always short of cash.

Also, some of the old respect for the

Cistercian Order is declining in parts of the country.

I don't doubt that 'our' monks are blameless, but it was disturbing when a

visitor from Tavistock last year told us of the abbot there, always drunk,

and 'leading a life detestable to God and man' - yet he still leads the convent.19

Some of our neighbours think it's time that we were free from the monastic houses altogether, but I can't see that happening in our lifetime.

This twin dove tile from the floor of the Monks' Choir is of the mosiac type, where the design is formed of separate pieces.

Formerly in the collection of Kenneth Beaulah.

. . . next chapter

Home Page

CHAPTERS

Chapter 1 ~

Chapter 2 ~

Chapter 3 ~

Chapter 4

Chapter 5 ~

Chapter 6 ~

Chapter 7 ~

Chapter 8

Chapter 9 ~

Chapter 10 ~

Chapter 11 ~

Chapter 12

Notes

1 The Cistercians, known as 'White Monks' because of their white habits.

2 Thomas Blashill: Sutton-in-Holderness, p.90

3 Sketch from former collection of WFW

4 'Our Father'

5 Revd G A Balleine: The Layman's History of the Church of England, p.40

6 Revd C Cox: The Annals of the Abbey of Meaux, p.21 - ERAS, Vol.1

7 C Foster: The Estates of Meaux (dissertation for MA, Leeds)

8 Cox, p.22

9 This twin dove tile from the floor of the Monks' Choir is of the

mosaic type, where the design is formed of separate pieces. Formerly in the collection of Kenneth Beaulah. (photograph)

10 George Poulson - History & Antiquities of the Seignory of Holderness, p.309. This biography of Edward III appears on the Chartulary of the Abbey of Meaux preserved in the British Museum. Somewhat damaged, it was in the collection of Sir Thomas Cotton, whose library was partly destroyed by fire.

11 the right to hunt.

12 'Activities of the Cistercians' - exhibition at Wimpole Hall, Cambridge

13 Elizabeth Eames: A 13th Century Tile Kiln Site at North Grange, Meaux

14 Cox: op.cit.

15 Aelred, the saintly abbot of Rievaulx from 1147-1167.

16 Tony McAleavy: Life in a Medieval Abbey, p.18

17 Cox, op.cit.

18 C Foster, op.cit.

19 Balleine, op.cit.

|

SUTTON

SUTTON