SUTTON

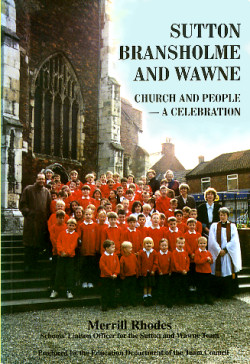

SUTTONBRANSHOLME & WAWNE Church & People - a celebration by Merrill Rhodes |

|

Home Page Distribution of land - Sir Arthur Ashe and

the Windhams of Felbrigg Hall and Waghen - Lord Hotham and Waghen Ferry - The

Alfords, Trusloves, Daltons and Watsons - The New Church - Strange Bequests - Incumbents

and Ejected Ministers - The Quakers - Non-jurors - Charitable Trusts; Leonard

Chamberlain and Ann Watson The Dissolution opened up vast areas of land which,

having been in ecclesiastical hands for centuries, were now in the hands of the

Crown and up for re-distribution. Important East Riding families such as the Alfords immediately began buying up leases for land. The large estate of Meaux Abbey in Sutton, worth nearly £16 a year, was leased by Lancelot Alford of Meaux as early as 1540, and the Alfords held the land until the mid-17th century.1

After the suppression of the college of St James in 1547, the rectory of Sutton was granted to Sir Michael Stanhope. However he was executed in 1552, and later

the rectory was also let to the Alfords.2 In 1629, much land in Waghen was sold or mortgaged by

Charles I to the Corporation of the City of London. It then consisted of 3,338 acres of land and marsh. From earliest times, Waghen had two

land-owners; Lord of the Manor and the Chancellor of St Peter's, York (York

Minster), thus it had the Manor of Waghen and St Peter's Liberty - later

Rectory Manor. From 1651 onwards Sir Joseph Ashe (1617-1686), a

wealthy London merchant who traded with the Low Countries,3 began buying land in Waghen, gradually

adding most of the rest of the Manor, and the lease of Rectory Manor. Sir Joseph was MP for Downtown, Wiltshire,

and he had holdings in other parts of the country, especially Twickenham. He supported Charles I financially during

the Civil War, and was later awarded a baronetcy. In 1652 he bought 7½ acres 'in a dale overflowne called Lowlands in Waghen alias Wane.'4

Sir Joseph presumably never lived permanently in the village (his home was in Twickenham), though he was responsible for further drainage projects. During the 1670s, he set up windmills for pumping water, and the drained carrs were sown with rape and oats. A few years later, Sir Joseph re-directed the waters of the Eschedike in a further attempt to drain the marshes. Drainage continued to be a problem for many years. Even after 1846 the aptly-named William

Leake, as the occupier of Rectory Farm, was reported to York as 'a very

respectable, intelligent and industrious man, but if in times like the present

he continues to keep all the Low Land in an Arable state .... he must be a considerable loser .... Some of the Land in Grass already is very wet, and ought to be drained.'5 Sir Joseph Ashe's eldest daughter Katherine

(1652-1729) married William Windham (1647-89) of Felbrigg Hall in Norfolk, in

1669. Portrait of Katherine by Lely, at Felbrigg, by kind permission of The

NT She was 'gay, generous, warm-hearted, a devoted wife,

a loving but thoroughly sensible mother.'6 It was a sound marriage in every way.

William was only 18 when he inherited the estate, and 'his wife's

generous portion, and the benefit of her father's experience and advice, proved

invaluable to Windham during the difficulties of the early years.' The couple had eleven children, eight of

whom survived to adulthood. They named their eldest son Ashe (older folk in Wawne remember his namesake, his great

great great nephew, Ashe Windham, as the 'Major' or 'Squire' in the early years

of the 20th century). Portrait of Ashe Windham by Sir Godfrey Kneller, Felbrigg, by kind permission of The

National Trust Katherine's husband, William, was only 42 when he

died. She wrote, 'My Dear Dear Husband left me having made me Hapy 20 years.' Katherine took on the running of the estate for the next 40 years; she

was lively and intelligent, and wrote a book on Cookery and Housekeeping, a

'fascinating record of a wealthy family's diet at the period.'7 Katherine took in to live with her family

her niece, Martha. Her son, Joseph, married Martha, and from this couple descended the Windhams of Wawne. On 8 January 1700 Sir James Ashe,

Katherine's brother and Martha's father, 'a very feeble man'8, bought up 'the lease

of the parish, rectory and parsonage of Waghen, and the manor of Waghen, also

the rent of 16s 8d. from St James Chappell in Sutton.'9 On Sir James' death, Martha transferred the land to her husband Joseph,

who adopted the surname of Ashe. In 1734 they had the manor of Waghen, with '18 messuages, 21 cottages, 20 barns,

30 stables, 20 gardens, 10 orchards, 220 acres of land, 767 acres meadow, 950

acres pasture, 780 acres fen ground, 100 acres furze and heath, and a passage

over the River Hull in Waghen and Sutton'.10

All in all, a fair parcel of land, 4,576 acres - and an interesting record of the land use in Waghen at that time. A hand-operated ferry over the Hull at Wawne was

established in ancient times. Henry

Arundel, Archbishop of York (1147-1153), gave to the monks of Meaux all his

lands in Waghen and the ferry. During the Civil War (1642-49) it helped

seal the fate of Sir John Hotham. As

Governor of Hull, his refusal to allow Charles I into the town on 22 April

1642, is well documented. Later, when

he and his son sought to deliver the town to the King, his son was

arrested. Hearing of this, Sir John

fled from Hull towards Waghen. Reaching

the river bank, he shouted for the ferryman, but was unable to rouse him. Whether the ferryman was absent or wished to

avoid trouble is not known, but the fugitive fled on to Beverley where his

enemies cornered him. On 15 July 1643

both father and son were sent to the Tower and were later decapitated, as

'traitors to the Commonwealth'. For

years afterwards, Sutton and Stoneferry were filled with soldiers whom they had

to maintain with slender hope of recompense. Peter Alford of Sutton died in 1566. He left to his godson, Edward Truslove, a

young cow; to Mrs John Truslove a feather bed, a pair of sheets and a pair of

blankets; to each of her children 'two yowes' (ewes); and a grey 'meare' to a

friend. The probate inventories of this period often record gifts of household goods and farm stock. Edward Truslove kept his lease of Keingley

(Kenley), Waghen, but lived in the Rectory House at Sutton. By his will of 1609, he left to his wife

'half his household stuff in his house at Sutton, certain horses and draft oxe,

his greatest silver salt, his greatest silver bowl, and his gilded bowl

standing upon 'Artemes of Lyons'.11 When the last lord of Sutton, Sir Thomas, died before

1389, without heir, the master and the chaplains of the college became the most

important people in Sutton. The manor itself became fragmented, resulting in the acquisition of land by several

owners.12 Thomas Dalton, thrice Mayor of Hull,

acquired from 1563 onwards, many messuages and cottages, free fishing in Sutton

Marr, and did most to ‘gather together the fragments.’13 As well as a large share in the Manor of Sutton, he acquired the

Hastings Manor or Berewic, and may have lived in a manor house on his

property. More than a century later John

Dalton, dying in 1685, left his 'mannor of Hastinges' to his brother, Thomas,

who in turn left it to his wife Elizabeth (Wytham) in 1700. Edward Truslove's son or grandson, John of Keingley,

married Elizabeth Watson of Stoneferry in 1650. Elizabeth's brother Thomas lived at the White House in Stoneferry,14 and left a

considerable estate, a good part of which passed to Elizabeth in 1665. Blashill believes that this was a share of

the original Manor. Elizabeth died in

1690, leaving the White House to her children and grandchildren, in

shares. By 1709, Mrs Ann Watson

(apparently no relation of Thomas Watson) had bought up most of the shares, now

part of the Watson's Charity.15 After the Dissolution, it appears that Wawne church

fell into a state of disrepair without the monks to support it, for in 1567 the

painted rood loft and the windows were in decay, and the 'Bible torn in several

places.' The porch, probably of the Perpendicular period, fell down in 1578 and had to be re-built.

Four years later the vicarage house was being used as a barn for cattle; and by 1596 the chancel was dilapidated.16 It seems, though, that pews had been

installed in the nave by this time, for when new seating was introduced in the 1820s, two old pews bore the date,

1590.17 Churchwardens were very important in the community. They had to keep the church in repair, see that folk attended, and that they behaved reverently. They would, if necessary, visit the ale-houses in the village and

force the people to attend worship.18 At this time, the altar was usually brought from the

east end into the body of the church, and people received Communion kneeling in

their pews. Attendance was compulsory, including twenty-two Holy Days, upon a fine of twelve pence. When James I came to the throne in 1603, and it became

clear that he would continue with the Protestant church, the fanatical Roman

Catholic, Guy Fawkes, plotted with others to blow up Parliament. Fawkes was, of course, executed, but the

plot was symptomatic of the continuing unrest throughout the country, and the Church

of England, the Romanists and Puritans carried on fighting their respective corners. People vehemently laid down certain conditions in

their wills - like Arthur Harper of Sutton who left a legacy in 1631, but only

if .... a: It is desired that X11 Bybles be bestowed in X11 of ye poorest families

within the parish and that in every such family there be one can distinctly

read the same to the rest of the family and at least once every day there be

read two psalmes and a chapter . . . b: Every Sabbath day in the Forenoon

12 penny loaves of sweet and Good Bread of Wheat be set in some convenient

place in the Church or Chancel ... to be given after morning prayers and Sermon to X11 of the most aged and impotent

persons ...... but if any of those poore appointed shall absent themselves any Sabbath day from divine Service and

Sermon and warning given twice at their home then that bread to be taken from

them . . . c: In Remembrance of God's great Mercy and Deliverance of the whole land

from that monstrous and horrible treason of those bloody papists Guy Fawkes and

his confederates every fifth day of November everie good subject to God and the

King should repaire to ye parish Church and there hear Divine Service and

Sermon .... and after such thanksgiving and worship of God there may be

provided for 40 poore children a small dinner for which shall be allowed

thirteen shillings and four pence and for a Dinner for ye Minister and

Churchwardens and Overseers of the poore, six shillings and eight pence, and to

ye preacher for his Sermon six shillings and eight pence .... 19 It is not known what happened to the dinners on 5th

November nearly 400 years later - but it would no doubt gladden dear Arthur

Harper's heart to see our roaring bonfires. John Spofford, Sutton incumbent from 1626 to 1633, and

a Puritan, was determined to steer his own course. He was the first to write

the parish registers in English; he disliked the Prayer Book and refused to

read prayers on holy days, Wednesdays and Fridays.20 Mr Harper may indeed have been one of

his two churchwardens who in 1627 were presented for not reporting their curate

for these misdemeanours. But the Revd Spofford pushed his luck too far; soon

after Arthur Harper died, the incumbent was dismissed for 'refusing to wear a

surplice four times a year.' Dakins Fletcher was appointed curate in 1633 and

managed to survive through the Commonwealth, and well into the reign of Charles

II. The streets were full of rejoicing when the re-instated monarch rode

through the streets of London on his 30th birthday in 1660, following

Cromwell's Puritan rule.21

However, only two years later, another curate of

Sutton, Josiah Holdsworth, was also ejected from the living. On 24 August,

known as 'Black Bartholomew', all non-conforming ministers who could not

conscientiously give their assent and consent to all in the Prayer Book, were

turned out of ministry. A graduate of Cambridge, Holdsworth endured further

deprivation after leaving Sutton; his followers at Heckmondwike 'meet not in

the day but in the night for these several months.'22 He was 'a man of great piety, sincerity, strictness and industry for the

good of souls'. Holdsworth's struggles against the intolerance of the age ended

in an early death. Quakers in Sutton and Waghen were also persecuted.

There were several farmers or cottagers who were Quakers and who refused to go

to church at all, preferring to meet together in one of their homes. They would

not pay church rate or tithes. The Elliker family were constant victims, perhaps

because they were farmers of considerable means, and could therefore stand

having their goods and animals impounded. In 1659 William Elliker refused to

pay 8s 6d for the upkeep of the church, and had a bacon flitch seized. In 1663,

William and his brother, Thomas, being summoned 'to go to the Steeple-house on

ye first day, and refusing, William Canum and Thomas Hodgson had them before

Hugh Lister, who demanded twelve pence apiece, and they refusing to pay it, he

granted a warrant for the Wardens to levy twelve pence apiece, for which they

took a pan worth 5s, of which "'they would 'a Returned threepence."'23 Some were beaten or even imprisoned. Thomas

Clarkson, a farmer from 'Pfarom House' (Fairholm Lane, Waghen) also suffered. After the Declaration of Indulgence in 1672, the

Quakers appointed for themselves a separate place where they could meet and

bury their dead, and thus a site in the Groves was chosen (now off the south

side of Hodgson Street). Site of Quaker Burial Ground, Hodgson Street From the registers, it would appear that they also had

another small burial ground 'in the Out-houses', somewhere in Stoneferry. 'Dak' Fletcher's name appears again in the registers

after the Restoration. He is buried in the church in 1674, joining the resting-place of the lords of the manor, the

wardens and chaplains, the Trusloves and the Daltons, and many well-to-do

Sutton parishioners. Sutton church was not to enjoy stability for long,

however. John Catlyn became the incumbent in 1689, but that was the year when

James II fled to France, and William of Orange claimed the English throne. Once again the church leaders were thrown

into confusion - whether to support the Divine Right of James, or to accept

William as King. The Archbishop, eight bishops and hundreds of clergy, including the Revd Catlyn, were evicted from

their vicarages. These non-jurors formed a new church which survived until 1805.

24 At the beginning of the 18th century, new

meeting-houses were registered for Independents or Presbyterians; Thomas Rogers

in 1719 and John Spivey in 1722 were registered in Sutton.25 A prominent Presbyterian, who died in 1716, founded

what appears to be the first school in Sutton. This was Leonard Chamberlain, a

member of the Bowl Alley Lane Chapel, who had inherited and married into

wealth. In his will, he remembered all the ministers who had been ejected from their livings for their Puritan views -

Josiah Holdsworth of Sutton, and the men of Hessle, Cottingham, Bridlington,

Selby and Shipton. By trade a draper in Hull's market place, Chamberlain left

generous and important bequests. Portrait of Leonard Chamberlain. Although he probably never lived in Sutton, he owned a

good deal of land there. In his will he describes his property as consisting of two farms, one in Sutton, one in

Stoneferry, both occupied by Robert Parrott, containing two houses and three

closes. There were also 14½ acres of meadow in the Ings; a Pighill and four gates in Sutton New Ings; and four

Commons in Sutton. There were, too, a farmhouse and garth, with a Land Common, and also a Pighill, which adjoined

land of Mr Henry Cocke (now Church Street); and three garths where three houses

had formerly stood, adjoining the farm house, with three commons belonging to

them. The farm lands comprised 11½ acres in Sutton, apart from that in Clough Field and Stoneferry. The estate at

Stoneferry comprised the farmhouse, etc, and 77 acres of land.26 The terms of Mr Chamberlain's will directed that from

the rents of the Sutton and Stoneferry farms, the sum of £5 annually was to be

paid to the schoolmaster of Sutton 'to teach and learn to read well 20 of the

children of the poorest people in Sutton and Stoneferry, of what persuasion or

denomination soever.' Archbishop Herring's Visitation Returns of 1743 indicate

that this was the only school in Sutton at that time: 'There is a School endow'd with five

pounds a Year, for teaching Twenty poor Children, who are duly instructed in ye

Church Catechism.' The British School erected in 1850 was then endowed

with the sum of £15 from the funds of Chamberlain's Charity.27 This school was

probably situated on the site of the present Providence Cottages, and was

associated with the Primitive Methodist chapel there.28 Chamberlain left money for almshouses in Sutton,

although these were not erected until 1800 and 1804. They were built for six and four people respectively, at a cost

of £631, for eight widows and two widowers, each having a house and garden and

3 shillings weekly. Chamberlain almshouses, College Street, 1960 In 1954 some of the almshouses, those built in 1800,

were replaced by a two-storey block comprising 12 flats. In 1999 these have

been demolished, and new bungalows are to be built. Six further houses were modernised in 1964, the accommodation

being reduced to four. A decade later,

dwellings in Chamberlain Close were erected, six single bungalows and four for

married couples. Wall Plaque on Homes The benefactor also left eight shillings per annum for

a sermon to be preached on Sutton Feast Day. Though Blashill states that 'the sum has never been claimed', the

minister of the Park Street Unitarian Church does preach at Sutton Methodist

Church, two sermons annually, on the Monday of Sutton Feast Day (25 July, Feast

of St James) and at Christmas. It may seem curious that when Leonard Chamberlain's

wife, Catherine, died in 1697, her body was interred in the tiny church at

Rowley, and he lies there with her. In 1638, the Revd Ezekiel Rogers of Rowley insisted on keeping the rules of

Puritanism strictly, and was ejected for it. Choosing escape rather than imprisonment, the vicar, accompanied by some

20 farmworkers, set sail for America, and there founded a settlement - Rowley,

Massachusetts. Doubtless, Leonard Chamberlain sympathised with this cause and thus chose a remote church in the

middle of fields as his burial place. He would have been surprised to see how busy today are the two roads

which bear his name in Sutton and Stoneferry. Watson Street in Sutton is named after Ann Watson who

also founded an important charitable trust. She requested that a monument to herself, her mother, husband Abraham

and their two sons, should be erected in Hedon church, where they are buried. Monument in Hedon church Ann Watson bequeathed all her estates at and near the

White House in Stoneferry, where she lived, to the ministers and churchwardens

of Sutton, Hedon and Holy Trinity in Hull, for the endowment of a hospital or

college, 'for clergymen's widows and clergymen's daughters, old maids, and for

a school for teaching children.' Each of the ladies was appointed a room, and 'each of

them might keep a cow if she should think it convenient.' The chamber over the parlour was appointed for

the schoolmistress, who was to teach knitting, spinning and sewing to ten girls

who could read, and therefore were able to read prayers. The girls were to be the children of poor

inhabitants in need of such assistance, and were to help the ladies with housework,

and receive twopence a week. The first schoolmistress was to be Mrs Watson's

friend, Jane Thomasin. The children were to go to Sutton Church on St James' Day, 25th July, and every Sunday when

there was a service, and they must learn the catechism. The minister of Sutton was to have £5 for

his sermon on St James' Day.29 The White House in Stoneferry was used as the college

until 1762, but then another almshouse was erected there, as being more

suitable for ten apartments. In 1816, the trustees built a new hospital or

college at Sutton, this being nearer the church, and 'more healthy' than Stoneferry, then described as 'a noxious

place.' The Revd Bromby, vicar of Hull from 1762, remembered the ladies being

carried on horseback from Stoneferry, seated behind the tenants of the college

estate. The new college, a two-storey grey brick building, was extended to the

east in a similar style, between the years 1840 and 1850. The Ladies of the College, outside the Church Room, c.1905 Ann Watson's will suggests an astute, intelligent lady,

meticulous in organisation. She left amongst her friends her plain gold ring,

with a 'posie' or motto in it, her gold ring without a posie, her clothes of

wool, linen and silk, and a pair of silver candlesticks. The

educational part of the charity was converted into a fund for school prizes and

maintenance grants in 1889, when both British and National Schools were well

established. The Charity still supports education work in the parish. Ann Watson's College, c.1905

Sampler worked by Sarah Jane Arksey of Gillshill cottage,

Home Page CHAPTERS Chapter 1 ~ Chapter 2 ~ Chapter 3 ~ Chapter 4 Chapter 5 ~ Chapter 6 ~ Chapter 7 ~ Chapter 8 Chapter 9 ~ Chapter 10 ~ Chapter 11 ~ Chapter 12 Notes

1 Keith Allison: Victoria County History; A History of the East Riding, p.473

2 Blashill, p. x

3 Felbrigg Hall: National Trust

4 Deeds - Brynmor Jones Library, University of Hull

5 Borthwick Institute of Historical Research, York

6 R W Ketton-Cremer: Felbrigg, the Story of a House, p.50

7 Felbrigg Hall: National Trust

8 Ketton-Cremer: Felbrigg

9 Deeds - Brynmor Jones

10 Ibid

11 Blashill, p.156

12 Allison, VCH, p.472

13 Blashill, p.158

14 near Ann Watson Street

15 Blashill, p.166

16 Borthwick Institute

17 Baines' Directory of 1822: 'the seats have never been renewed, and are much corroded by time.'

18 Balleine, p.128

19 Register of Burials

20 Allison, VCH, p.307

21 This monarch was well remembered by generations of schoolchildren in Sutton. Mary Salvidge recalls a

skipping rhyme popular at the Council School in the 1920s:

22 Revd Bryan Dale: Yorkshire Puritanism & Early Nonconformity

23 Blashill

24 Balleine

25 Allison: VCH

26 Chamberlain Will

27 Sheahan & Whellan

28 Deduced from Tithe Map, Census Returns and Deeds of contiguous property

29 Ann Watson Will

30 From the original kindly given by Mary Salvidge

|