Home Page

CHAPTER 5

Feast Days - Sutton before Enclosure

Enclosure Award, 1768 - Sutton Mills - Charles Pool

18th Century Waghen - The Overseers' Book

Sutton

held an annual Feast on the anniversary of the patron saint, St James, 25 July.

This was possibly a survival of one of two fairs mentioned in 1548-9. It is

likely that Miracle Plays were performed in the church in medieval times; it is

recorded that in 1442, the Mayor and Aldermen of Hull were 'entertained by the

Players' of Sutton.1

At Sutton Feast there were many stalls in the High Gate (now Church Street,

under the chestnut trees), with swings, roundabouts and perhaps a canvas

theatre.

On the Sunday nearest 25 July, a rough football match was played between the villagers

of Sutton and Wawne. The men would gather on the boundary bridge, the Foredyke,

the ball would be thrown up, and away would chase the men, all eager to get the

ball home to the village. This caused serious accidents, and eventually the

'game' was abandoned locally, remaining so for a generation.

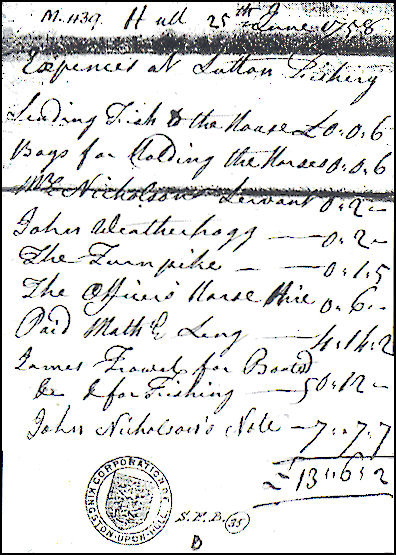

From at least the 17th century, an annual Fishery Feast was held on Midsummer Eve to

celebrate the Corporation of Hull's right to fish in two of the Sutton Marrs

known as the 'Fillings' and 'Old William's', near Castle Hill. It was a

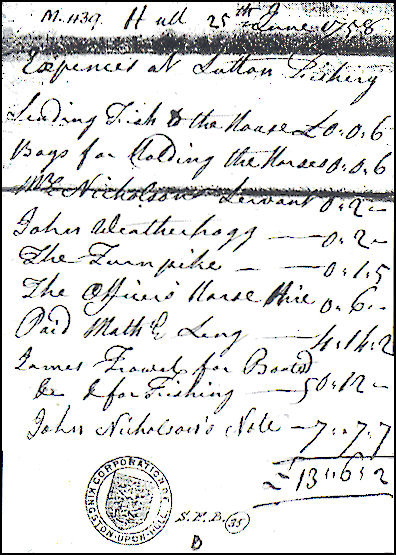

prestigious event. We can imagine a warm day on 21 June 1758 when the

Mayor and some members of the Corporation come to Sutton in procession. The

Mayor has a chaise and pair. The Town Clerk, the mace bearer, and three others,

ride horses hired for them at 6d for the day. Toll is paid at the Summergangs

turnpike; the toll-keeper makes out the bill for 1/5d.

When the party arrives in the Carr, where the road from Sutton crossed the

Frier-dike (Foredyke), their horses are looked after by boys who earn 6d for

their trouble. James Trowell, fisherman, is ready with four or five boats, and

the men draw the nets so as to drive the fish to places where they can be taken

out.

While the catch is being packed in baskets with cool leaves and despatched to the Inn

at Sutton in readiness for the feast, the Aldermen look over their farm at

Bransholm, idly listen to the complaints of their tenant, and then stroll on to

the village.

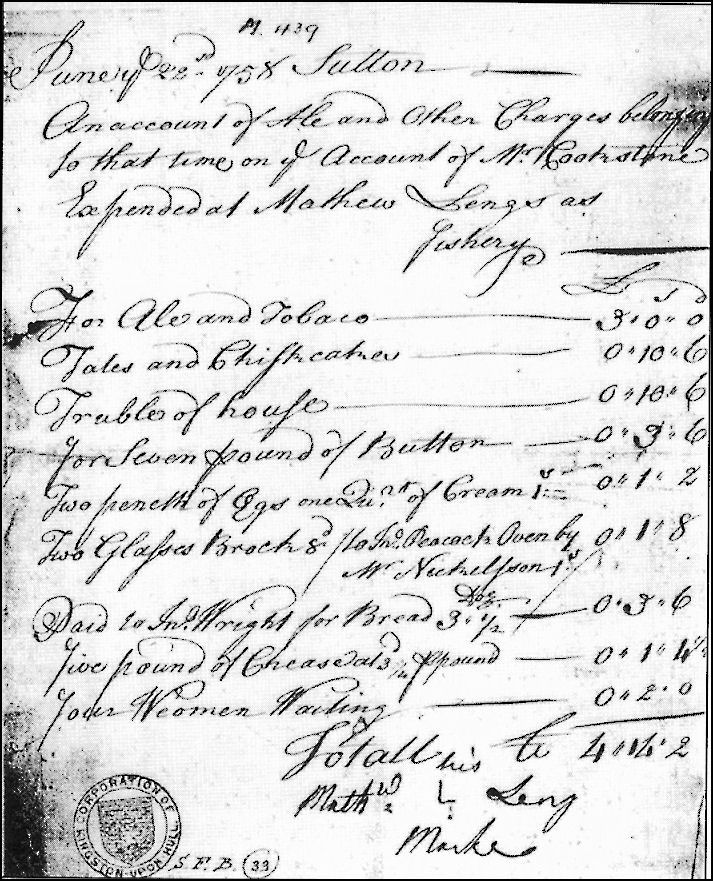

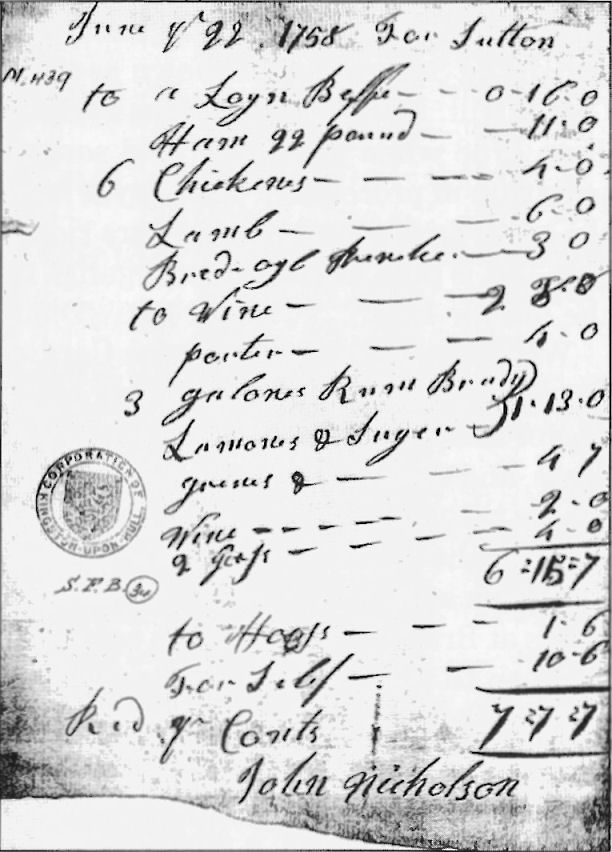

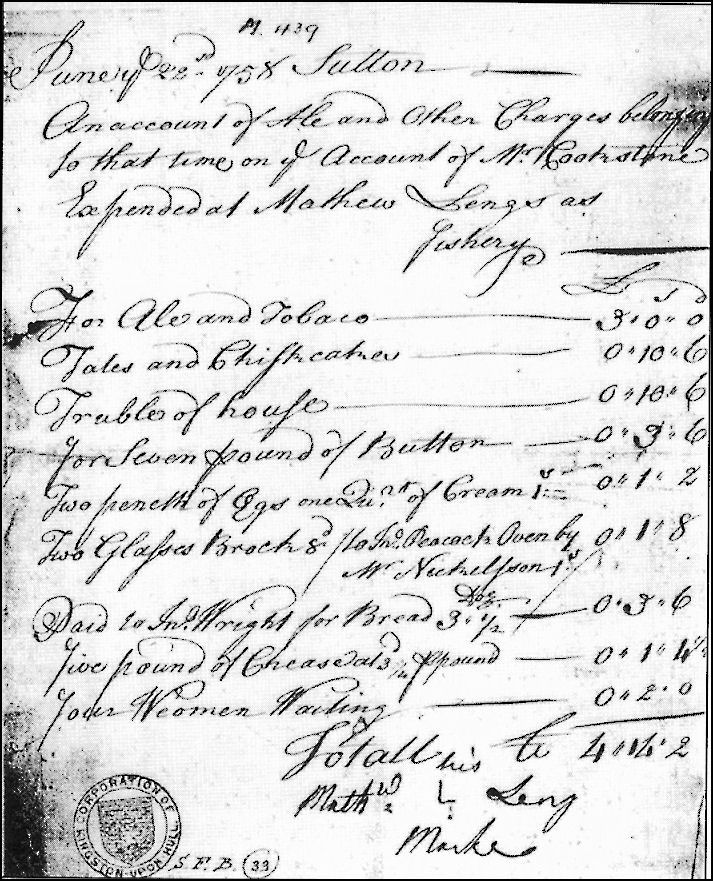

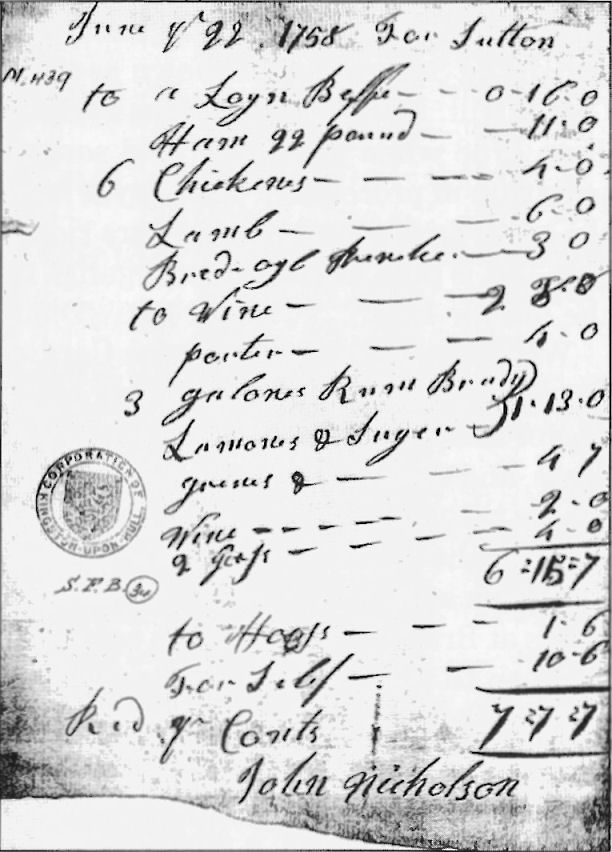

Here the more serious business of the day begins. John Nicholson, who supplies

refreshments at the Town Hall, has brought the necessary provisions: six and a

half gallons of wine; three gallons of rum and brandy; half a dozen chickens; a

stone of beef; and a quantity of lamb. To follow: 'tates and chisscakes.' These are only the extras, for the

meal is a fish supper, for which seven pounds of butter is needed to fry it!

Matthew Leng, our innkeeper, presents his bill for ale and tobacco, and 10/6d for his

'trouble of house'. 'Four Weomen Waiting' are paid 2/-. 'Two Glasses Brock' today add 1/8d, to make a

total of £4.14.2d. Our Matthew, who cannot write his name, makes his mark

- X - to claim his expenses. No doubt the whole village would share in the

Fishery Feast. Regretfully, it seems to have ceased at the time of Enclosure.

The Fishery Feast Receipts of 1758 ; click to expand 2

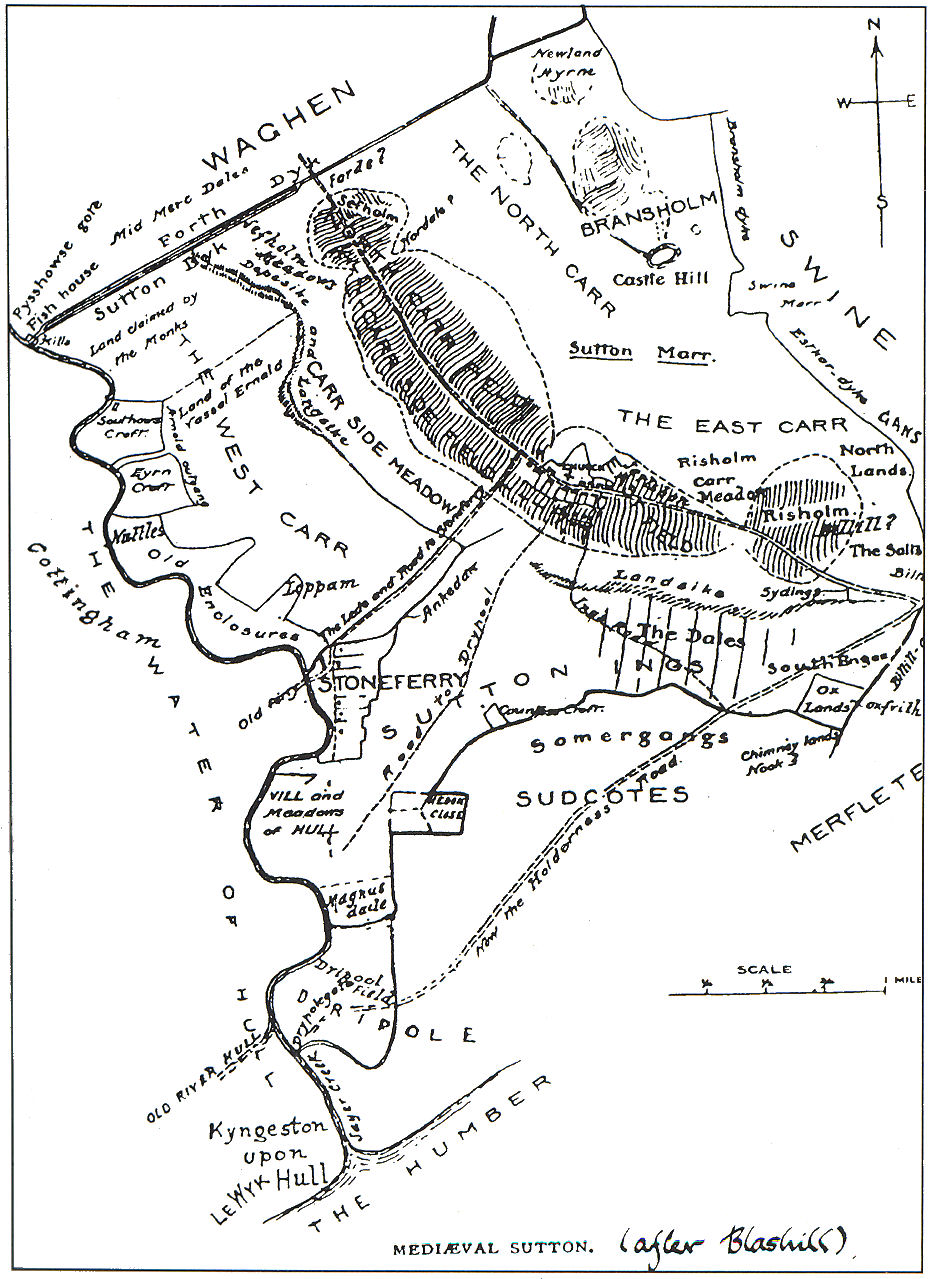

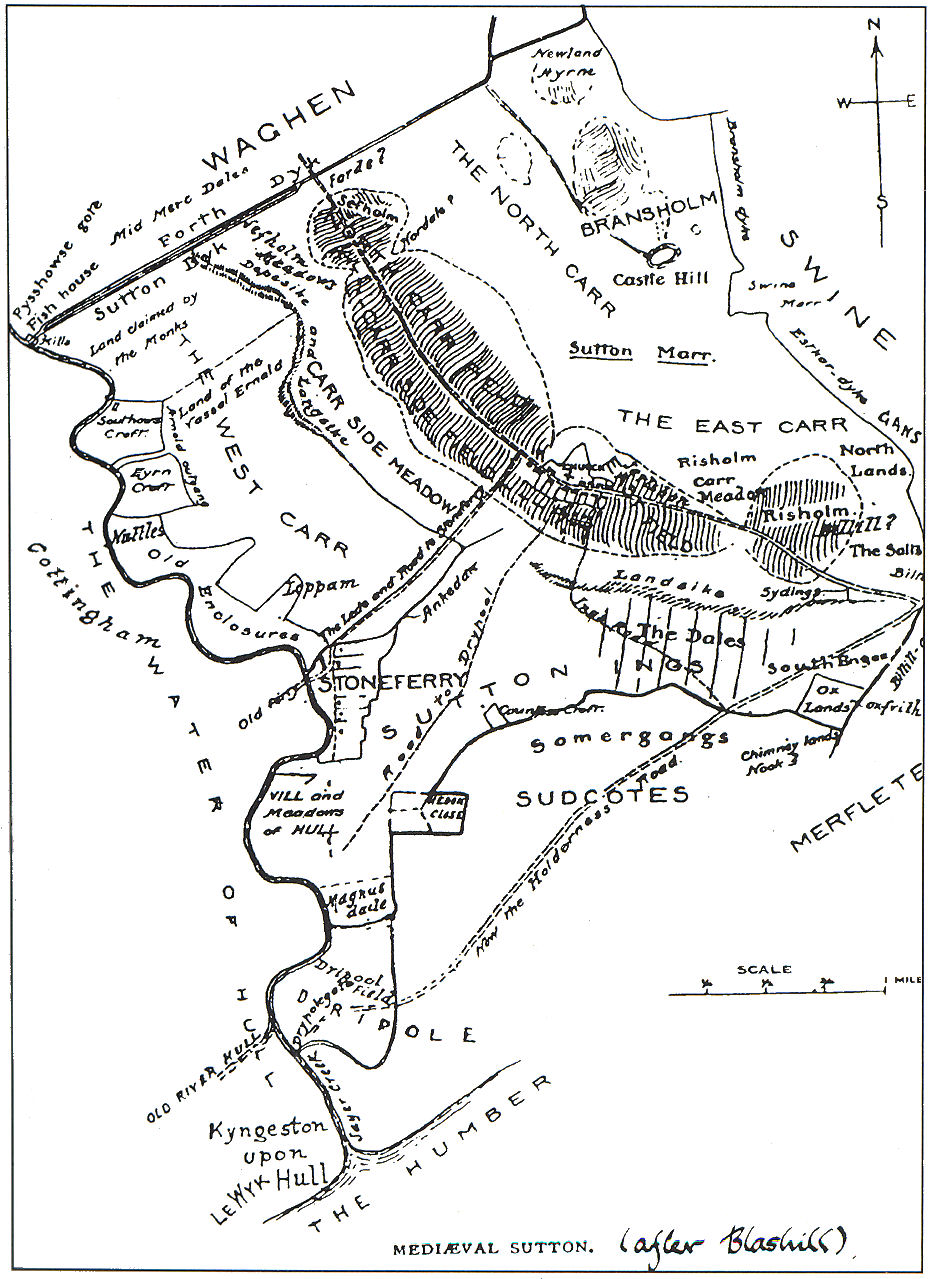

By the 17th century, improvements in drainage had opened up more acreage for crops

and husbandry, the open-field land stretching along the ridge, and sloping down

towards the meadows and carrs on north and south. As in most villages,

there were three chief fields; East Field, North Carr, and West Carr or Carr

Side Field. One of these would be growing a crop of wheat, another

patches of barley, oats, beans and peas, and the third lying fallow. These

fields were dotted with tofts and toftsteads.3 The better-quality pastures lay for the most part north of the ridge, including the area of

Bransholm. The carrs, the wettest and lowest areas, were used as common wastes.

Land-holders

enjoyed rights of two kinds:

a) 'Commons' applied to the fields, commonable meadows and wastes. In 1642 a

land-common was fixed at three beast-gates, and a house-common at

two-and-a-half. Each

beast-gate entitled the owner to turn out one 'great mouth' (e.g. cow, ox) or

four calves, or four ewe and lamb couples, or five wethers (male sheep). Two

beast-gates were needed for a horse to graze.

b) 'Beast-gate' - applied to the better-quality meadows and pastures. These

entitled great mouths to be turned into North lands, Bransholm, East Carr, and

the Salts4

(now Wilberforce College area).

The difficulty was that no man's land lay together; in 1613, for example, Nicholas

Cooke had land in Stoneferry, 'an acre of medowe in the Yngs of Sutton, four

acres of medowe lying in the East end of the same Yngs, a sixth part of ground

called Castle ringe, a sixth part of ground called Castle Hill, lying in

Bransholme, a sixth part of ground called Hallcoate Walls and four beastgates

in Bransholme all in the Lordship of Sutton.'5

From the church tower, say, the whole area surrounding the ridge would look like a

level plain, without a fence or house. Beyond the ridge, there remained

extensive marshes and carrs, and also, looking towards Swine, large pools such

as Sutton Marr. The memory of these watery lands survive in present-day names

like Bransholme (Braunceholm, Branzceholm, etc), an old Scandinavian word

meaning 'Brand's water-meadow'; Riseholm (Risholm) meaning 'water-meadow

overgrown with brushwood'; and Soffham (Sefholm) - 'the meadow overgrown with sedge.'

Because of the inconvenience of farming separate pieces of land scattered over the ings

and carrs and tillage fields, the farmers would live crowded together in Sutton

village, or on the slopping ridge. Two examples of simple, pre-Enclosure

farmsteads still exist in Lowgate.

Jessamine Cottage c1913 6

There

would be a shop and one or two ale-houses, probably on the same site as the

present Ship and Duke of York.7 There were a few cottages

occupied by the village tradesmen - blacksmith, wheelwright, tailor, weaver,

shoemaker, some of whom also owned farm land. In 1639 Robert Langdale, the

carpenter, had four beast-gates in Sutton.8

Map of Medieval Sutton and surrounding area,

after Blashill

Despite improved drainage and embankment, the parish was still flooded from time to

time, and sometimes footways were impassable. In 1764, from January to April,

the whole of the land between Bilton and Hull were flooded, and travel by boat

was the only option. New drains would have to be cut; this work coincided with Enclosure.

Tate's Drainage Plan of 1764

The Enclosure Award of 5 January 1768 shows evidence of great care and judgment in

allotting to each owner the land that lay most conveniently regarding his

farmsteads and ancient enclosures, though the owner could exchange small pieces

of land if he chose.

The

Award also dealt with public and private highways, and footways, and with the

drains. The public roads were staked out practically on the lines of the old

highways, straightening the irregularities that had been produced by the

traffic of centuries. The Map shows the familiar roads we know today -

Tween Dikes, Ings Road, Waghen Road, Castle Hill Road, Lowgate, High Street. By

the side of every highway a footway ran over the lands of the owners, so that

the person on foot was separated by hedge and ditch from the roads used by

vehicles and cattle. Every allotment had to be enclosed with hedge and ditch.

The landowner had to provide gates, stiles and planked bridges where the paths crossed the boundaries

between their fields. Many labourers were employed to build farmsteads on the

new areas of land. The ancient water-courses, now called public drains,

were also adopted by the commissioners, and the new drains cut.

Enclosure Map of Sutton, and Allotments - 1768

The

tenant farmer could now live and work on his land, and manage it as he liked.

He could enrich his ground for cattle. Root crops and green crops could be

introduced. The improved tillage could be used for wheat, in view of

rising costs. Enclosure made farming much more convenient and economical, and

land more valuable, and not many folk in Sutton lost the right to graze an

animal or two, as happened elsewhere.

In

a few years, the view from the church tower would be very different. Directly

below stood the poorhouse, erected in 1757, and reliant on the church for its

beneficence. Inside, a man and his wife, known for their 'sobriety and

industry', taught the poor to spin wool. Some would take up employment in the

cotton and flax mills on the river bank at Stoneferry, or in the oil mills,

bleaching houses and timber yards, and so would escape to 'normality', though

before the '10-Hour Day' Act, life was hard. Others were not so lucky, for the

poorhouse had an extension built in 1814. In 1826 Mrs Dunderdale was

'governess' of the Sutton house. The curriculum is not recorded, but by virtue

of the Poor Law Commission of 1835, children of the workhouses were taught

reading, writing, religion and other 'fitting' instruction, for three hours a

day.9

The

early post-Enclosure farms include Castle Hill, allotted to Thomas Broadley;

Low Bransholme occupied by Benjamin Blaydes, Junior; Soffham, left to Charles

Pool; and High Bransholme, Lamwath, and Salts House.

A

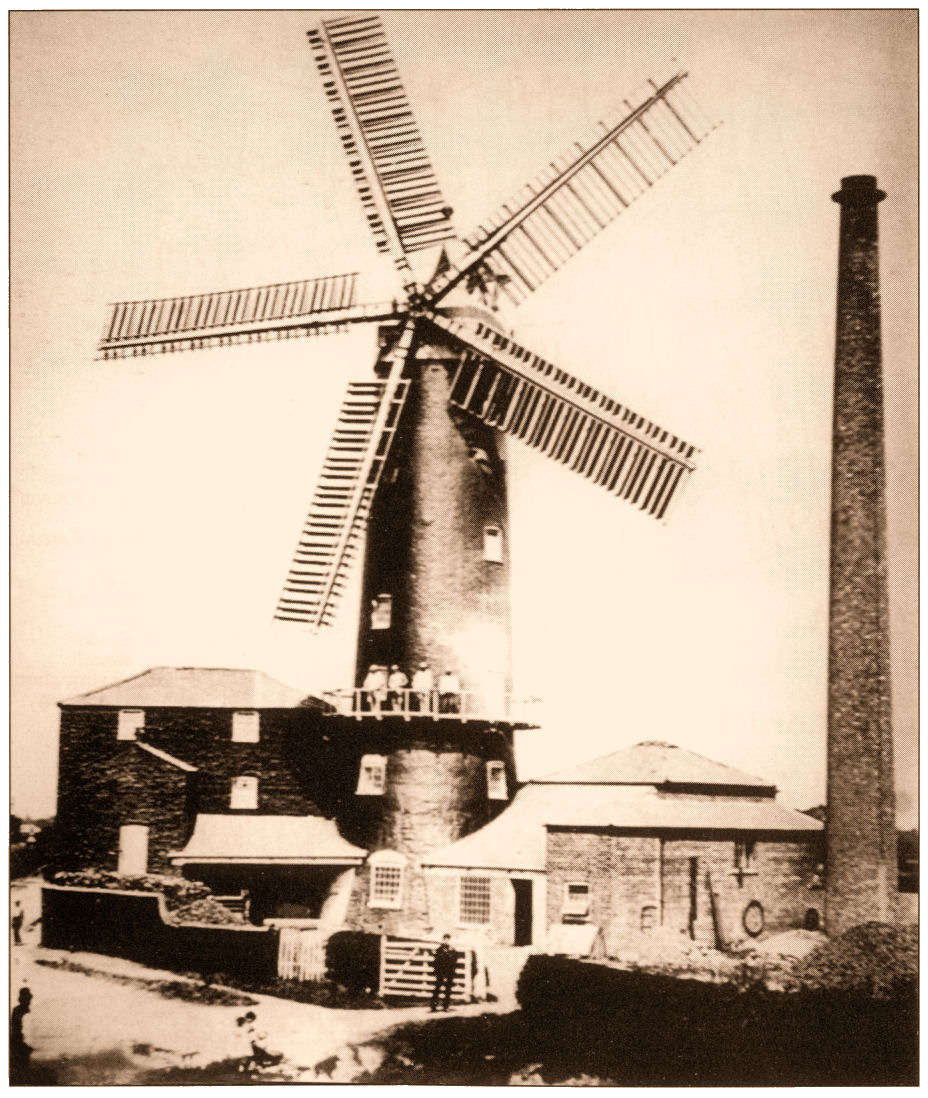

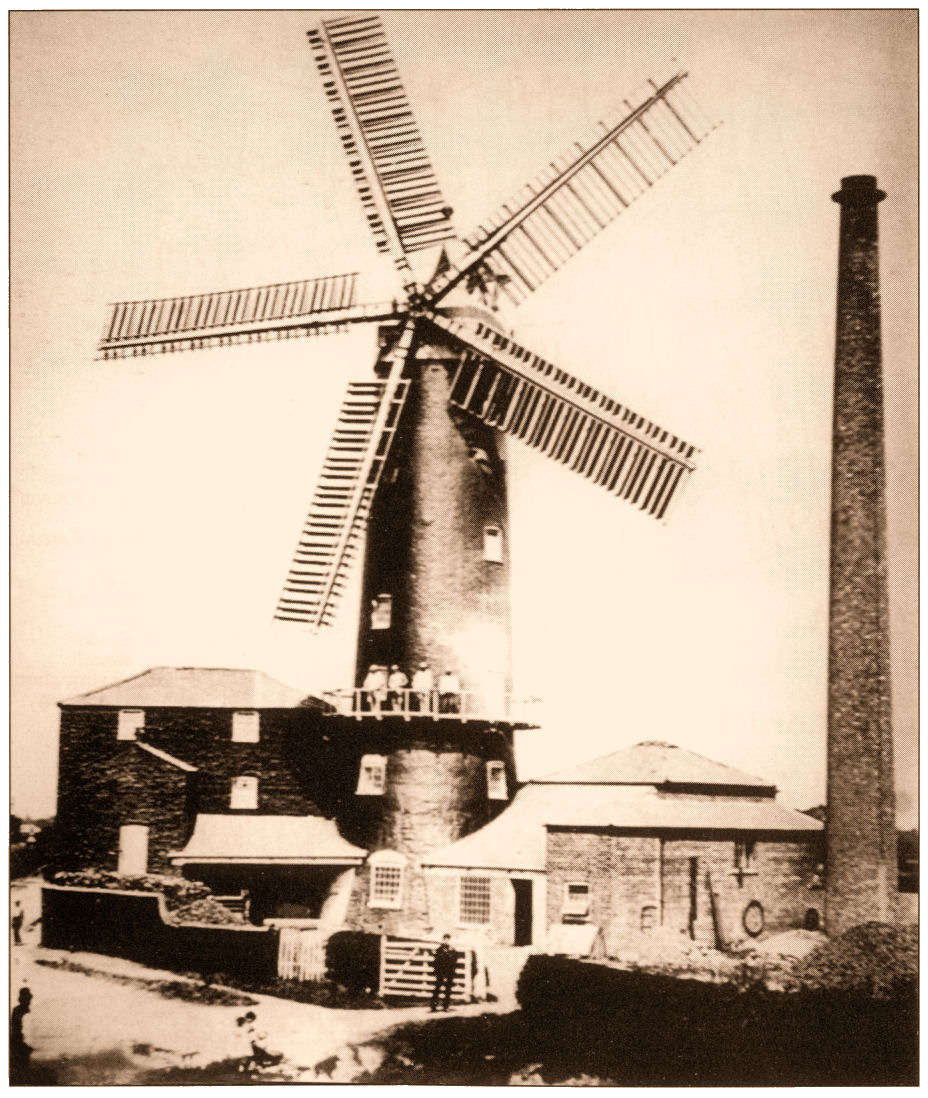

little way down Wawne Road10

the corn mill on Windmill Hill dominated the landscape. This was built in 1715

by William Munby, to replace the Munbys' original mill in the village. The area

being largely agricultural, the mill served the farmers well, cleaning,

preparing, grinding and dressing corn and flour. Originally of four sails, the

mill appears to have five by 1803,11 and was raised to seven floors, with a gallery

above the third floor.

Sutton Mill

Steam

machinery was added, and the land included three cottages and stabling for four

horses. Evidently tracks ran round the side and round to the landing bays

(these were later converted into cottages, now known as Woodbine Cottages). Mrs Guy, who lived in

one in the 1960s, recalls the cellar at the back, where people had to stoop to

enter the doorway. It would seem that the rulleys bringing the corn would

offshoot the load into the landing bay. The Guys unearthed large pieces of mill

stone and iron. Three mill cottages (now Ivy

Cottages) stand on the other side of Wawne Road, which is

unexpected, but originally the footway to Wawne ran behind the mill,12 so the cottages were close to the

mill. These

cottages were built in 1853, number 1 being larger than the others, so was

occupied by the foreman; it has two bedrooms. Number 2 is smaller, and

number 3 smaller still. The coalhouse and toilets were in the backyard, and, as

was often the custom, the gardens still lie across

the frontage of the cottages, number 3 being nearest the dwellings.13 A path ran round the

back, which could suggest a lane where perhaps a few mill workers lived. The mid 18th

century Census records list people living in 'Mill Lane'.

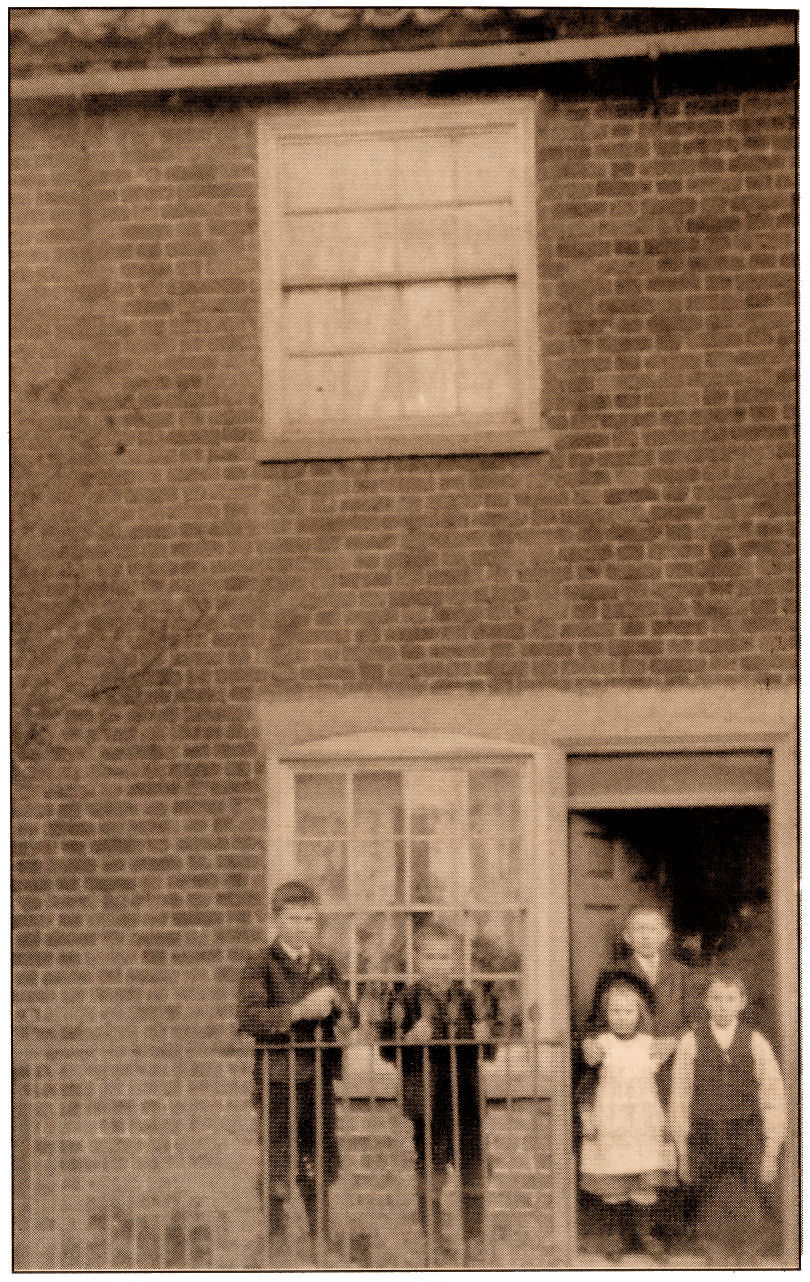

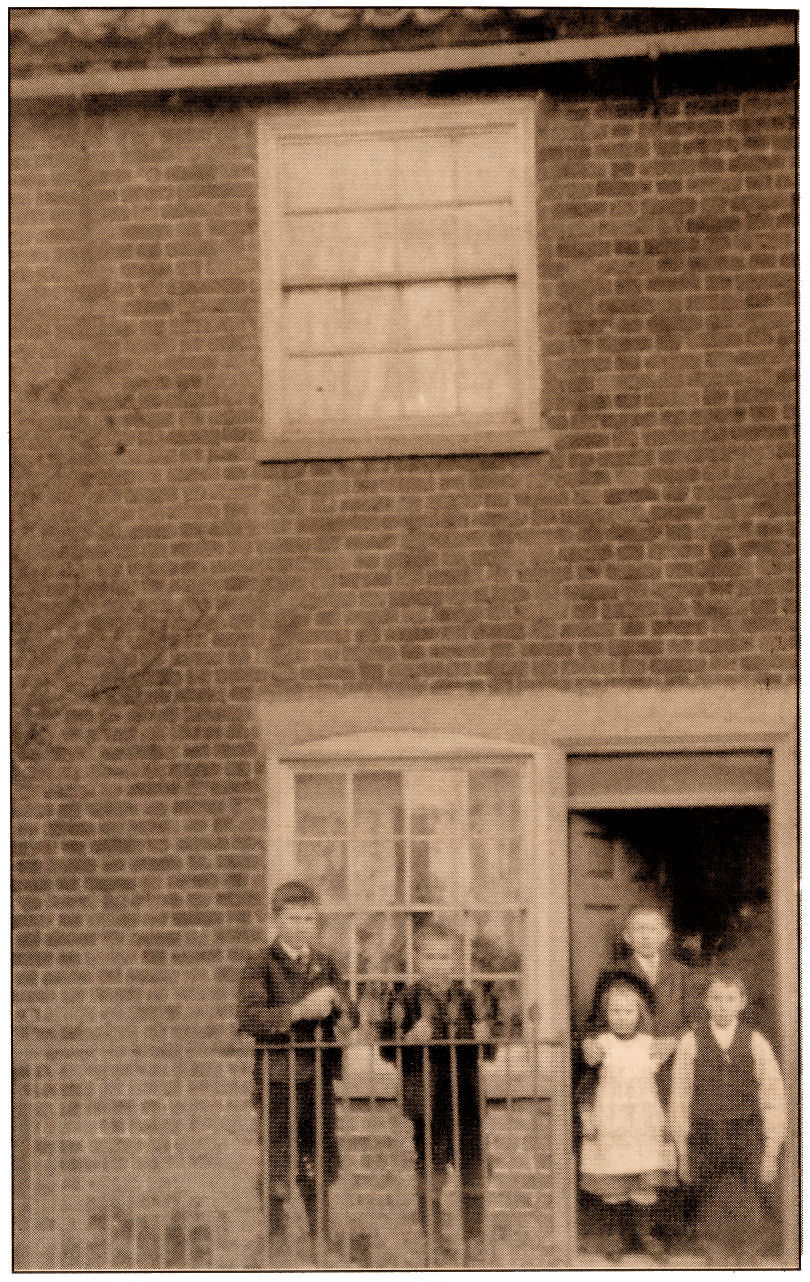

The Robinson family of Ivy Cottages, c1914

Disastrously,

on the afternoon of Monday, 21 April, 1884, smoke filled the skies for miles

around - a fire had broken out in the neck of the mill. The men working there

tried to put out the fire with hand buckets, but by the time a horse-drawn fire

engine from Hull arrived, it was too late and the mill was completely destroyed.

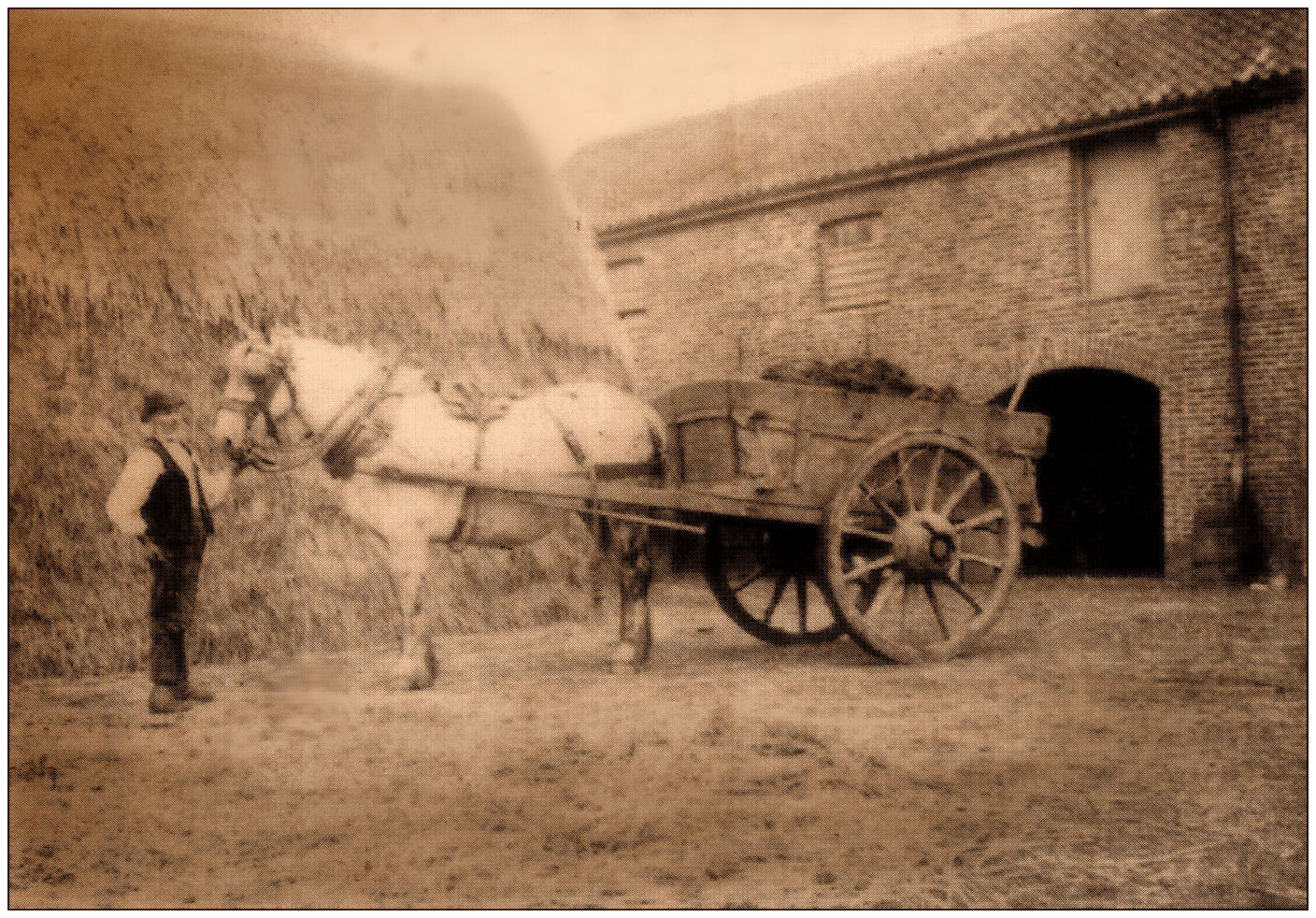

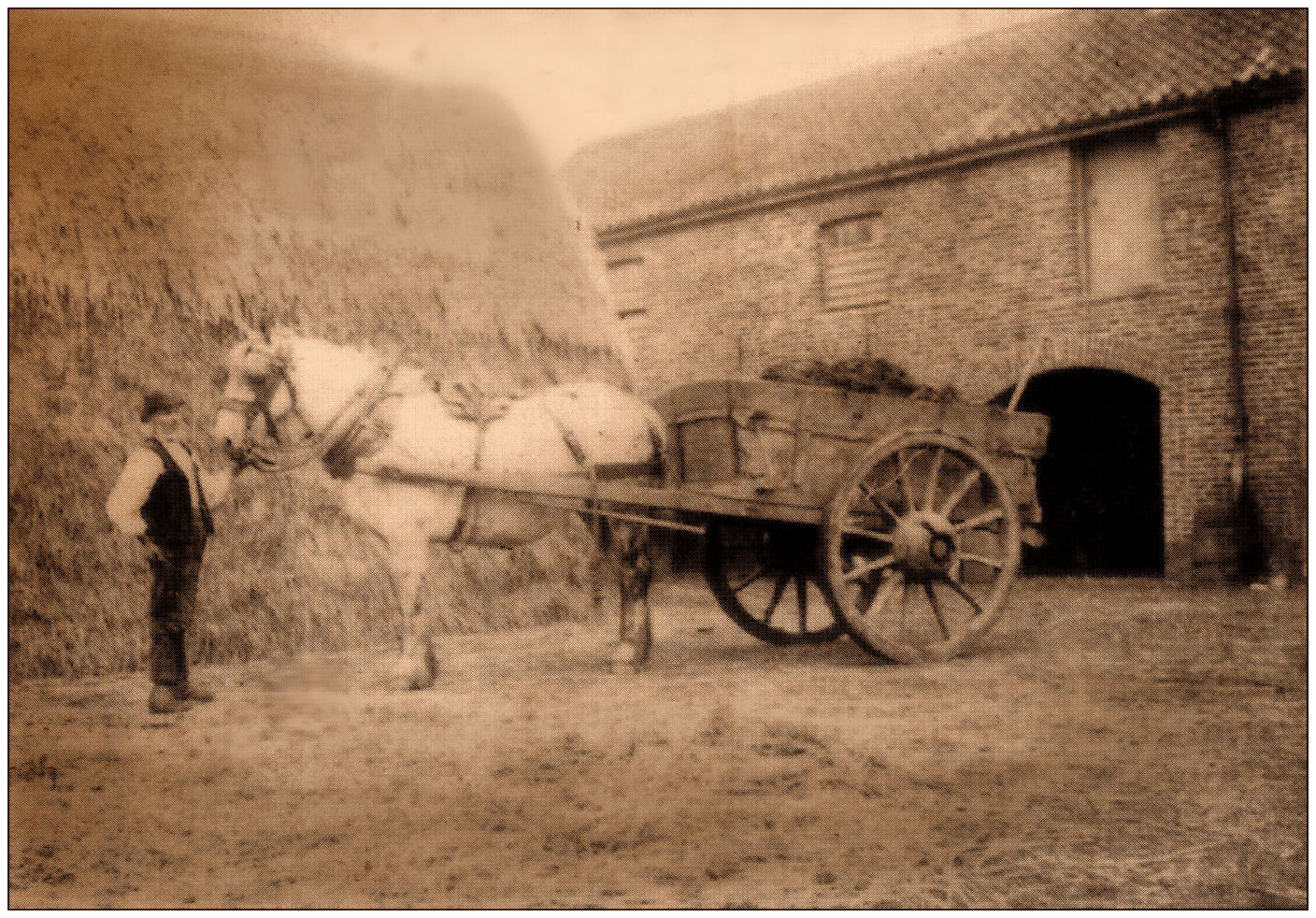

One of these men who fought so bravely was William Goodin, aged 34, whose back was

terribly scarred with burns. He never had a regular job again,

but worked occasionally, as in the photograph, on one of the Bransholme farms.

According to his granddaughter,14

who lived next door in Rutland Terrace: 'my grandfather was a lovely man,

always cheerful, good-tempered. I can remember he walked very painfully with

the aid of two sticks. Despite this, he walked to Wesleyan Chapel every Sunday

morning, hail, rain or snow. When he could no longer work, his son built

him a little place in the back garden, the 'shop' as we called it, and he set

up as a cobbler, repairing boots and shoes. He sat at his bench all day, and

had a chair where old friends would come and talk to him . . . '

William Goodin

The

miller at the time of the fire was George Brownbridge Barker (1831-1910). He

lived in Chesney House next to the mill (now Barton House). His grandson,

George Ronald Barker, attended Sutton School.

George - 2nd row, 2nd rt. Mr Topham headmaster,

c.1898

G B Barker had a daughter, Emily Annie, who lived at Chesney House until her

father died, and later moved to 'Highgate', the house opposite (now a Dentist's

surgery). She owned the house and the three mill cottages until 1918. Miss Barker

is remembered as being small and stout, with strong features and short, white

hair. She was organist of the Wesleyan chapel, and gave music lessons; Robert

Beckett paid 6d per lesson in the 1920s, travelling from Skirlaugh by train.15 Emily Barker

died in 1939.16

F.C. Scott

There were other mills in Sutton in the late 18th century. The Deeds of The Olives, later The Hollies, and now Greenacre, in Saltshouse Road, show

that before this listed house was built in around 1810, a brick windmill

occupied the site. This was probably the mill which somehow killed Jenny

Farthing, spinster, in 1783.17

The

Hollies

was the home of Frederick Arthur Scott, of solicitors Scott & Cooper,

from 1879 until 1925. His father was the architect Sir G. G. Scott, who was

responsible for restoring St Mary's Church, Lowgate, between 1861 and 1863.

Frederick Scott was President of the Reading Room and a churchwarden.

Further down Saltshouse Road stood another mill. This belonged to Charles Pool, who had

his house at East Mount, on the site of the Princess Royal hospital. In 1778 he

built himself a Drainage Mill worked by sails to drain his land. He was by then

a very influential man, a merchant, and Mayor and Sheriff of Hull for several

years. His grandfather was Hugh Mason, the owner of the rectory and tithes, who

settled some of his land and tithes on Charles in 1736. (The poet William

Mason, was Charles' cousin.) As noted on his monument in Sutton Church, Charles

Pool worked tirelessly against 'the prejudices of ages' towards enclosing the

land. By the award of 1768 he was 'owner of all the tithes', together with the

tithe farmstead (Enclosure, allotment, 138).

Memorial Tablet to Charles Pool

(he never spelt his name with an 'e')

As impropriators of the church, he and Mary Mason had, in 1763, organised a

full-scale repair of the chancel roof, selling the lead and re-roofing with

slate. Later, Pool gave the pinnacles for the tower, which, together with the

south wall, was covered with pebble-dash. The churchyard was extended.

Charles Pool held several properties in the parish, including a brick house, with barn,

stable and garth, on the site of Highfield, next to Godolphin Hall, left to him

in 1769 by Jane Wilkinson (Enclosure,

allotment 100), and a further 76 acres of tillage. He also owned

the farm of Soffham, which he called 'Weston Farm', but the original name

prevailed. It was advertised for sale in 1787 when the proximity of Sutton

drain was said to be advantageous, and, indeed, Blashill writes that there were

times 'when the best teams could not draw a load of corn through the mire from

the farmstead to the road.' Charles Pool died in 1798, and R.C. Broadley bought

Soffham, adding to his already substantial lands.

During the 18th century the incumbent could be responsible for several livings, and

thus might not visit for months - 'for a quarter of a century the village never

saw its vicar, except on one occasion . . . '18 In 1740 the incumbent of Wawne,

Steven Metcalf, was rejected for 'ignorance in divinity'. From that year until

1789 Arthur Robinson, Vicar of Holy Trinity, served as incumbent of our parish,

employing a curate for Wawne, Sutton and Marfleet. Robinson paid his curate,

Joseph Dawson, £45 a year, which even Archbishop Drummond thought sparse. He

upset Dawson still further by endeavouring to persuade him to live in Wawne,

but the curate protested that the dwelling was 'a wretched abode', let to two

labourers who could offer him 'neither diet nor lodging', and as for Wawne

itself - there was 'no entertainment in the town.'19 Dawson suspected that Robinson really

wanted him out, for as the Archbishop sharply remarked, 'Dawson is a dissenter.'

Wawne's history as monastic land probably led to early enclosure, as the land would

have been used as farms worked by the lay-brothers and later, hired workers.

The open fields around the village were enclosed by private agreement by Sir

Joseph Ashe in the late 17th century. The hearth tax returns of 1667 record Thomas

Grantham's house as having 16 hearths - a messuage, then, of considerable size

with perhaps 10 or 12 rooms. Later, the Beharell family are seen

as well-to-do.20

Archbishop Herring's Visitation of 1743 show just 43 families in Wawne at that time, with

about 30 children attending school.

The Overseers' Book began in 1760, so it is possible that the Poor House was built

about that time.21

The building was thatched, and must have been fairly large, for it took a

certain George Hall nine days to thatch it. An entry for 1770 is detailed: William

Heart agrees to take on as servant an 11 year old orphan girl, Elizabeth

Pharoh, and she is allocated these items of clothing; shoes, stays, aprons,

pettycoats, pattons, stocking, 2 coats, 2 shifts, cloak, 6 caps, hat, and

handkerchiefs.22

Sadly, Elizabeth died after only a few months.

Payments

were made for the upkeep of the poor and for the poorhouse by wealthier

villagers, especially in times of need; for a midwife; for the doctor; 'for

taking Hanna to Cherreburton'; for a chair for the workhouse; and for burying.

'Old William' was certainly looked after well; he was given a handkerchief;

tobacco, a quart of black beer; a quart of gin; mutton and beef; a pound of

brimston; and, finally, 6d for washing himself!

The arm of the law made its presence felt; as in most villages, Wawne had its

stocks in the 18th century, and the constable would frequently use them for

miscreants.

Entries in the accounts of Richard Consitt of Waghen and Robert Wise of Meaux,

churchwardens, in the latter half of the 18th century, include 7s 4d. to

Bricklayer and Laurence for Laying School Floor; 4s 0d for Dog Whipping;23

2d for Oil for Clock; 1s to Wm Biby for Cutting Weeds; 1s. to School-master for

Cleaning Steple; 9d. for a Base for the Pulpit.

The new incumbent of St Peter's, George Thompson, BA., arriving in 1789, was quick to

introduce the latest ideas in church music; there are references to

'Fidelstrings'; to rosin and bows needing re-hairing; to Sutton Singers; and

the grand sum of £1.13s 6d for the Singing Master, probably an itinerant man

eager to teach the new hymns. Possibly this fresh approach to worship staved

off the Methodists for a while longer! Two Methodist meeting houses had already

been established in Sutton by this time, but Wawne was to wait more than another

three decades before farmers Christopher Nicholson of Wawne, and William Smith

of Meaux, registered their barns for worship - in 1822 and 1823 respectively.

St Peter's Church, Wawne

. . . next

Home Page

CHAPTERS

Chapter 1 ~

Chapter 2 ~

Chapter 3 ~

Chapter 4

Chapter 5 ~

Chapter 6 ~

Chapter 7 ~

Chapter 8

Chapter 9 ~

Chapter 10 ~

Chapter 11 ~

Chapter 12

Notes

1 Blashill, p.131

2 Documents in Hull City Archives reproduced by permission of Hull City Council:

BRF6/800; BRF6/709; BRF6/797

3 Ibid, p.223

4 Allison: VCH

5 Hull City Archives

6 Thanks to Mr/s Fairbank

7 Both pubs feature old brickwork, and a splendid well lies beneath the snooker table in The Ship - formerly the back yard.

8 Hull City Archives

9 Peter Railton: Hull Schools in Victorian Times

10 Now the corner of Noddle Hill Way

11 Skidby Mill Archives

12 Blashill

13 Thanks to Mr/s Alexander

14 Beryl McGough (née Rowntree), now 87 but still working as a journalist in Adelaide, Australia, to whom I am indebted for much information and many anecdotes.

15 Doris Kirby (née Beckett)

16 Thanks to great-great-grandson of G B Barker, Peter Cook of Leeds, for details of the family.

17 Register of Burials

18 Balleine, p.186

19 Borthwick Institute of Historical Research, York

20 Mary Carrick, of Wawne, records several people of means living in the village in the 17th and early 18th centuries; and suggests that the population in 1671 may be as many as 410.

21 On the 1853 OS map, the Poorhouse is about 100 metres past Meaux Bridge on the right-hand side.

22 Churchwardens' accounts, E.R. Archives and Records Service.

23 Dogs in church were seen to be a nuisance. As well as this duty, the Dog Whipper also had the job of waking up the parishioners who fell asleep during the sermon. Occasionally, people would leave money in their wills to the Dog Whipper, so that he would be even more diligent in keeping the congregation awake!

|

SUTTON

SUTTON